Trigger Warning: The following blog discusses murder and death, and may be distressing to some readers.

A crime that shook the province

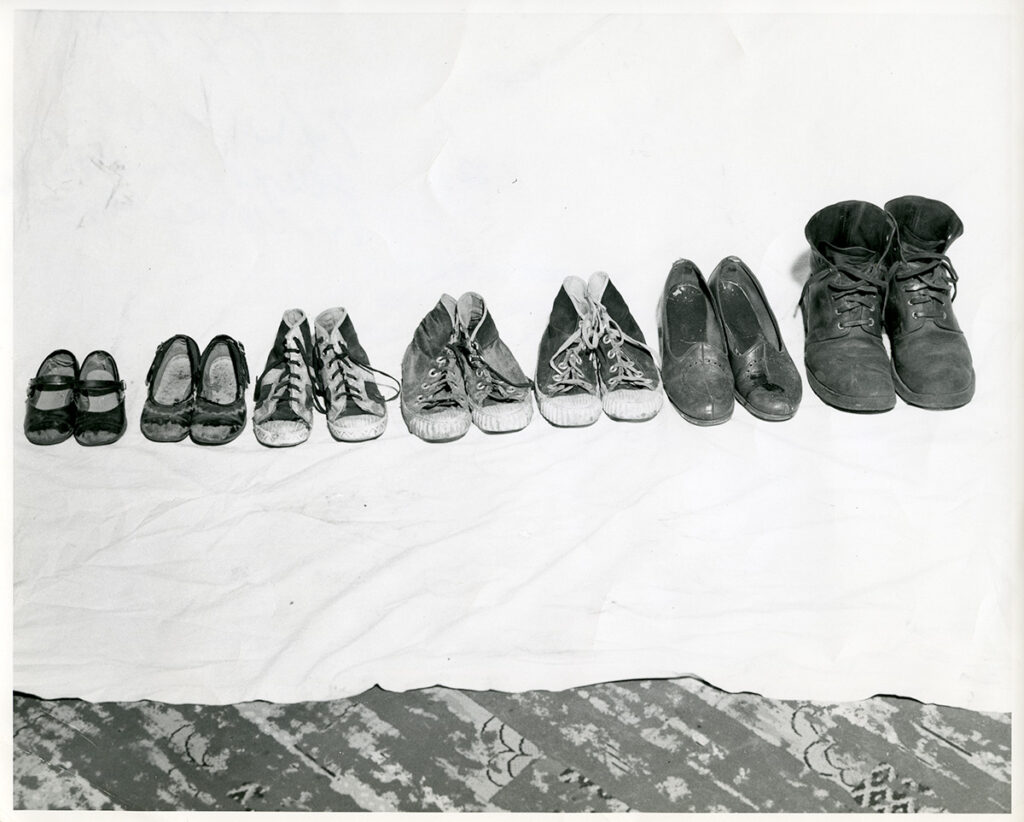

In the summer of 1959, the quiet prairie town of Stettler, Alberta, was shattered by a crime so horrific it would haunt the province for generations. On June 25, 1959, seven members of the Cook family—Raymond, his wife Daisy, and their five young children—were found murdered in their own home.

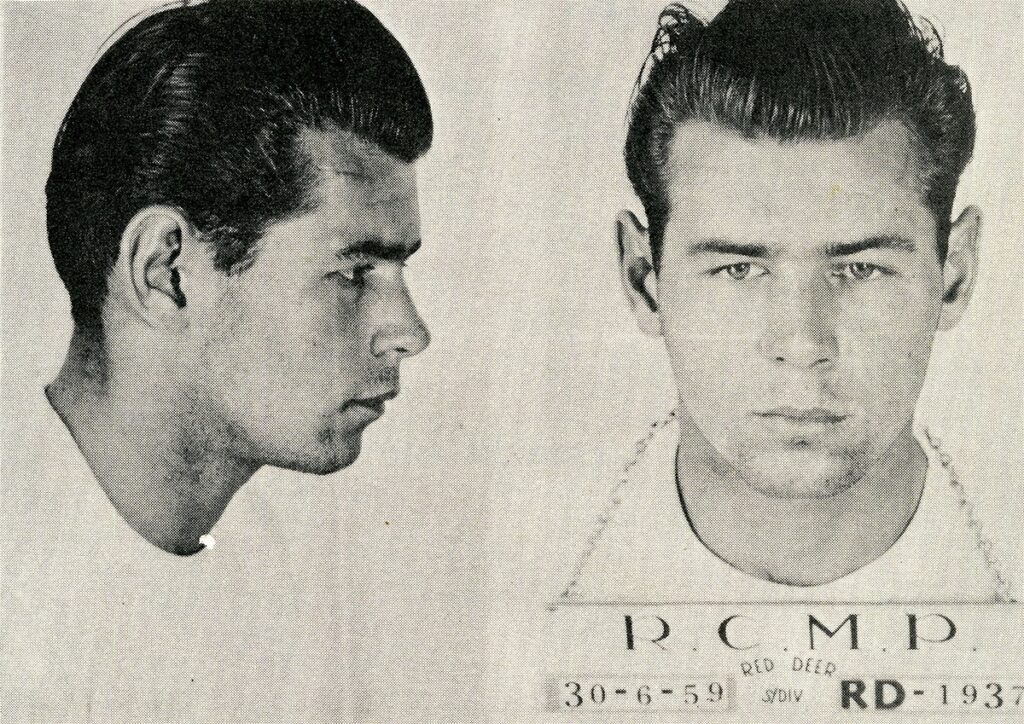

Suspicion quickly turned to 22-year-old Robert Raymond Cook, Raymond’s eldest son from a previous relationship. Robert was arrested days later while attempting to trade in the family car. Inside the vehicle, police discovered a chilling collection of items: children’s pyjamas, insurance papers, and the marriage certificate of his father and stepmother. Robert’s evasive stories only deepened the suspicion. Something was terribly wrong.

On June 28, the horrifying truth emerged: the seven bodies had been stuffed into the grease pit beneath the family’s garage.

What followed captivated the nation. While awaiting psychiatric evaluation, Robert escaped the Ponoka Mental Institution, stole a car, crashed it, and vanished into the Alberta countryside. The manhunt that followed was one of the largest in Alberta’s history, with over 100 RCMP officers, police dogs, militia, and aircraft searching tirelessly. Days later, Cook was found hiding in a pigsty near Bashaw.

Rather than try him for all seven murders, the Crown focused on a single charge—the death of his father—to expedite the trial. The first trial in Red Deer ended in a guilty verdict. After an appeal, a second trial in Edmonton reached the same conclusion. Cook was sentenced to hang.

On November 15, 1960, Robert Raymond Cook was executed in Fort Saskatchewan. It was Alberta’s last execution—and the second-last in Canadian history.

To this day, the Cook family murders remain one of Canada’s most disturbing crimes.

But this blog isn’t about Robert Cook.

His story has been told—by the media, in books, on stage.

Too often, these crimes are remembered by the names of those who committed them. We obsess over their motives, their madness, their final words. But we forget the names of those who ran toward the darkness—who searched fields, knocked on doors, and carried the burden of justice. We forget that for RCMP Members, even this harrowing case is just one chapter in a long, often thankless career.

This is Ted’s story.

Introducing Sergeant Theodore (Ted) P.J. Hesch (Ret.)

Ted Hesch was born in Ontario on May 16, 1937, the eldest of eight children—and the only boy among six younger sisters until he received a telegram from his father in 1957 announcing the birth of a baby brother.

“When I was a young fellow, probably 12 years old or thereabouts,” Ted recalled, “I had read books and stories about the RCMP. I thought then that this was the career for me. I knew a couple of fellows from my hometown who joined the Force. Some of the stories they told inspired me. It was hard to get in at that time, so I was very fortunate.”

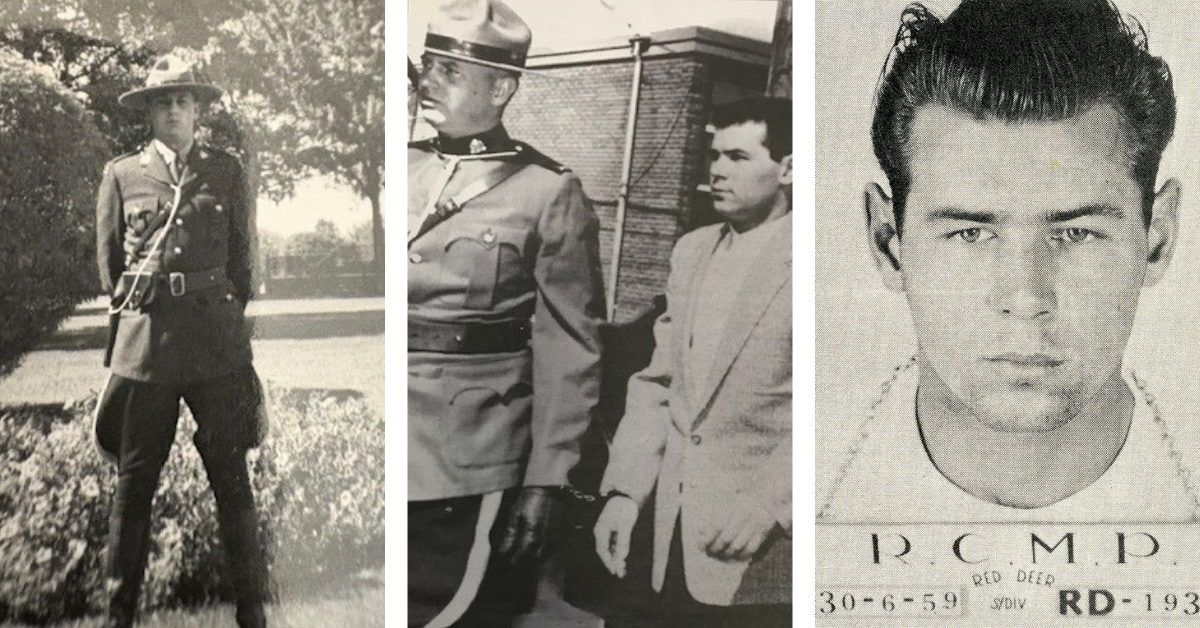

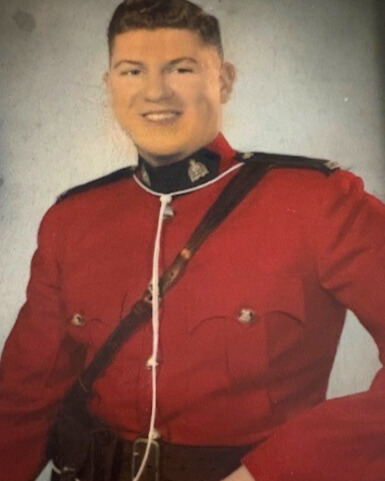

Ted dreamed of becoming an RCMP Member from a young age, making it official at just 19 years old

Ted joined the RCMP in June 1956 at just 19 years old. After graduating in early 1957, he received his regimental number: 19480. His first posting was with the Protective Branch in Ottawa, where he worked security at key institutions like Government House under Governor General Vincent Massey, the Bank of Canada, the Royal Canadian Mint, and Parliament Hill. He was also part of the security detail during Queen Elizabeth II’s visit in September 1957.

After his transfer to K Division (Alberta), Ted was posted in Edmonton, where he worked in the guardroom and later with the Criminal Intelligence Branch.

In 1958, he was stationed in Innisfail — the first of many rural postings across the province. Over the years, Ted served in Red Deer, Olds, Killam, Coronation, and Stettler, often as the only officer covering vast stretches of countryside. With no radio communication and hundreds of kilometres between calls, he relied on grit, instinct, and determination.

His work was as varied as it was demanding: investigating break-ins and thefts, responding to train and motor vehicle accidents, handling accidental and natural deaths, and enforcing everything from provincial statutes to the Criminal Code of Canada.

Ted’s role in the Cook case

Ted was alone at the Innisfail detachment on June 28, 1959, when the RCMP Sergeant from Stettler called. Seven bodies had just been found.

Ted was asked to notify the victims’ relatives—Raymond Cook’s mother and sister, who lived in a trailer park in Bowden.

“It was quite a thing for a young guy like me to have to tell them,” Ted said. “It was my first time.”

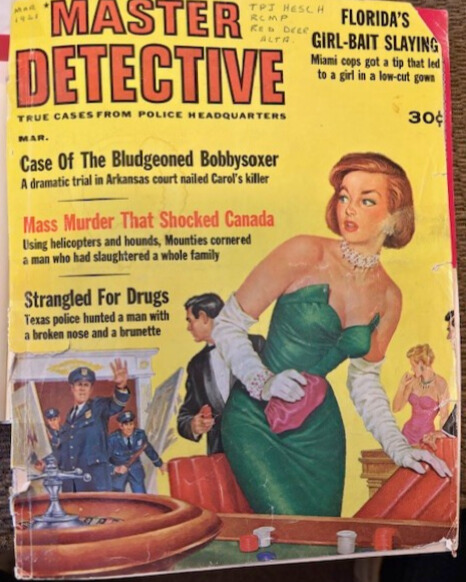

An issue of “Master Detective” magazine from Ted’s personal collection, covering the Robert Raymond Cook murders

He couldn’t share details, as the case was active. The emotional weight of that task stayed with him.

On July 11, Ted heard over the radio that Cook had escaped from the Ponoka Mental Institution. “A friend of mine was involved in the chase. He fired his revolver, and the bullet passed through the back window and out the front—just missing Cook.”

Cook crashed the vehicle and fled. Meanwhile, Ted was one of the few Members securing the shaken community around Innisfail and Bowden. “We were tired and working 24 hours a day, checking vehicles in the event Cook returned to the area to harm his grandmother,” he said. “The whole community was scared. The whole of central Alberta was frightened. Some rural families even joined together, arming themselves with guns in the event Cook showed up at their residences.”

Resources were sparse. “We had no rifles, no shotguns. Just revolvers, one police car, and one set of handcuffs for the entire detachment.”

Thanks to reinforcements from across Alberta and beyond, Cook was recaptured on July 13 near Bashaw.

Up close and personal

After Cook was recaptured, Ted thought his role in the case was finished—but fate had a different plan.

After being transferred to Red Deer to join the RCMP Highway Patrol, Ted found himself working on the top floor of the Federal Building. Just next door was a small holding cell—and inside it, awaiting trial, was Cook.

Ted (left) and Cst. Shewchuk (right) escorting Robert Raymond Cook (middle) to Court on charge of murder in Red Deer, Alberta (1959)

Ted, along with Constable C.W. Thompson, was tasked with guarding Cook during the nighttime hours. “Cook was a cool and chilling character,” Ted later recalled. “He never showed a hint of remorse.”

For ten tense days, Ted’s duties included escorting Cook across the street to the Red Deer courthouse, a slow, weighted walk under the wary eyes of the town.

Cook was ultimately convicted of his father’s murder—not once, but twice—and sentenced to hang each time.

One case of thousands

While the Cook case left a permanent mark on Ted and the country, this was only one example of thousands of challenges and triumphs throughout his career.

One frigid January evening in 1964, Ted had just finished a curling match when he was dispatched to a potential murder scene south of Stettler. It began with a suspicious traffic stop at the U.S. border. The driver—posing under a false identity—was Donald Scheerschmidt, who had murdered a local bachelor named Coulton Mackey.

At Mackey’s remote home, Ted and his team forced their way inside. “The place was ramshackled. A .22 rifle and a Rosary were on the floor. There was no heat—ice had formed in the sink.”

Scheerschmidt confessed and led the police to a 160-acre plot that was empty with the exception of a well in the middle. The water within the well was frozen to ground level, and Mackey’s body was placed on top of the ice. Ted and RCMP Constable A.R. Wilson guarded the site overnight—in -30°C weather, relying on the car heater for warmth.

A newspaper clipping from the Edmonton Journal (May 1, 1964)

After the investigation was complete, the still-frozen body was placed in the trunk of a police car. The image of Mackey’s body, frozen in a fetal position with a cigarette holder between his teeth, has stayed with Ted for life.

That case never made national headlines like the Cook case did. But like so many career experiences, it left a permanent impression on Ted.

A legacy to remember

Ted’s work didn’t end with the Cook or Scheerschmidt case — in fact, far from it. His career grew into a testament of leadership under pressure and resilience in the face of constant change.

In 1965, Ted transferred from Stettler to Camrose, where he was tasked with launching a new highway patrol unit. For nine months, he worked the highways alone, laying the foundation until two additional constables could join him.

His steady leadership did not go unnoticed. In 1967, Ted was promoted to Corporal, and just a year later, he took charge of a six-man highway patrol team in Stony Plain, west of Edmonton. Stony Plain was a demanding post, with the busy No. 16 Highway presenting daily challenges.

Ted continued to rise through the ranks. After four years in Stony Plain, he was in charge of the Whitecourt Town Detail, second in command at the detachment. From there, he was promoted to Sergeant at the Calgary Detachment, overseeing operations that included policing the Tsuu T’ina Nation.

Ted’s leadership journey culminated at one of the RCMP’s busiest posts: the Calgary Airport Detachment. As Operational Non-Commissioned Officer, he managed a team of 32 officers. His focus on training, mentorship, and operational excellence left a lasting mark. Years of experience in crisis management had honed his ability to keep one of Canada’s busiest airports safe and secure.

On October 1, 1986, Ted retired after over 30 years of service.

Our unsung heroes

Though his assignments were varied and often challenging, one thing remained constant: Ted showed up with professionalism, humility, and an unwavering commitment to protect and serve.

Behind every badge, there’s a family making sacrifices too. Transfers often came with only a few days’ notice, uprooting Ted’s growing family time and time again. Each new post meant the stress of finding housing, building new routines — and sometimes buying a home he barely had time to live in.

Through it all, Ted and his wife Yvonne — now married for 62 years — built a life grounded in service, resilience, and love. Today they live in Calgary, often visiting with their three children, Cathy, Kelly, and Trent, along with their five grandsons.

In telling Ted’s story, we remember what’s too often forgotten: that behind the cases that make the news are officers who carry their memory and weight long after the headlines fade, and who serve our country in ways we will never see.

This blog is a tribute—not to infamy, but to the integrity of service.

To every Member who has faced the darkness in service of others. To Members, and all police officers like Ted.